After deciding to leave the mountains due to the changing of the seasons, we headed to Lima to catch a flight to Santiago, Chile, where we would start the next phase of our trip into Patagonia. But first, during these last few weeks in Peru, we took in as many sights as possible in and around Lima.

Ruins of Caral

From the coastal town of Barranca we visited the archeological site of Caral. This involved a harrowing van ride with a driver who, over the years, had lost his mastery of the clutch (all vehicles we saw in Perú used manual transmissions, even large buses), and who rolled wildly through intersections on a wing and a prayer with his horn blaring. Caral is thought to be the oldest center of civilization in the Americas, contemporaneous with the construction of the Egyptian pyramids. Caral was a large urban center with numerous pyramidal temples that were, until recently, covered by sand and therefore hidden from view while in plain sight. Caral was the largest of over 20 similar complexes found in the same river valley. It’s awesome to contemplate how many yet undiscovered archeological treasures might remain hidden throughout Perú.

Riding the coast toward Lima

After two days of riding into strong headwinds along the bleak, trash-strewn, sandy Panamerican coastal highway, we arrived on the outskirts of Lima. Rather than spending one more night in a small-town hospedaje, just to get up the next day and ride 35 km with dense industrial truck traffic through sketchy neighborhoods into the city, we hired a young driver with a van to deliver us that evening directly to our guesthouse in Lima’s Miraflores neighborhood. This neighborhood was clean, modern, and quiet - like nowhere else in Perú we’d been. It was our introduction to the idea that there are two Perús: there is Lima, the capital and economic engine of the country, and there is everywhere else.

Lima

Lima is home to 9 million people – more than a quarter of the national population. We heard from locals that the population boom began in the late 20th century, as people from around the country were fleeing violence in their communities, and it is clear that the number continues to grow as Peruvians migrate here seeking economic opportunities. As in the U.S., there is a huge economic chasm in Lima between the wealthy and the poor, but we also perceive a massive cultural chasm (potentially even greater than in the US). Rural Peruvians, traveling from the mountains or the jungle, must find Lima to be like a foreign country: confounding, hyper-technological and radically out of scale.

Contrasts: infrastructure

Upon our arrival in Lima we (norteamericanos) were struck by tree-lined streets, well-maintained public infrastructure, handicap accessibility, and bike lanes complete with bicyclists! We were stunned to see “no honking” signs, since loud, incessant vehicle honking is part of the language in the rest of the county. Lima’s affluent neighborhoods were filled with single-occupant vehicles — not permitted were the three-wheeled mototaxis that are the main means of local travel in most of rural Perú (and in Lima's poorer quarters). Given this, we were were a bit surprised by the traffic chaos that still reigned at unsignalled road intersections, and the complete lack of priority given to pedestrians.

Throughout Perú, even in cities, we saw indigenous people wearing their traditional clothing styles – except in Lima, where we didn’t see any.

Contrasts: dogs

In Lima, dogs were being walked on leashes, some were even wearing sweaters. Although we're used to this at home, this was shocking after being on the road. While riding in rural Perú (and Colombia and Ecuador) it seemed that almost every home and many businesses had 3 to 5 unfenced dogs that invariably chased us down the road. Here’s a short video of just how annoying dogs can be to bike tourers.

Contrasts: food

And the food… Perú is known throughout South America for its excellent cuisine, but that quality and variety is found mainly in Lima and other cities of scale. In Lima, restaurants distinguish themselves with creative menus, and amazing flavors. In rural Perú, the limited menu options were always the same. We lived on chicken soup, hard-cooked gristly meat, rotisserie chicken or trout, always served with potatoes and white rice. On lucky days there were beans or lentils. We shunned any salad garnish after each getting sick twice, and instead sought out Chinese food (called “chifa” in Peru) as a way to get more vegetables.

Old town with new friends

Much of our time in Lima was shared with different members of the Hiromoto family – all cousins of Julie Hiromoto, Clark’s friend and colleague in sustainable architecture and planning, whose Peruvian parents emigrated to the U.S. and raised her there. With one cousin, Daniel, and his wife, Alicia, we walked through the Spanish colonial-era center of the city and through its Chinatown, and were treated to lunch at a crowded restaurant that was clearly a long-time neighborhood fixture. Lima’s old town was characterized by multiple, grand public plazas, each with an elaborate sculptural centerpiece, crowded with thousands of people, and surrounded by beautiful colonial architecture with many buildings that have ornate, dark, 2nd-story enclosed wooden balconies.

We met another Hiromoto cousin, Gabi, during her workday and were treated to a delicious nouveau-Japanese lunch – sushi rolls with spicy sauces. Her day-to-day routine sounded very similar to that of an urban working parent in the U.S. Another cousin, Javier, happened to be a dentist, and after giving us our 6-month dental cleanings, he treated us to a fantastic Peruvian lunch of ceviche and pisco drinks. In addition to their extraordinary generosity, all of the Hiromotos we met spoke near-perfect English, allowing for some rich, and very enlightening conversations.

LUM exhibit

Yet another cousin, Claudia, a young architect (as is her husband, Alejandro), gave us a tour of the remarkable LUM museum, an architectural project on which Alejandro worked. The museum, a “place of memory, tolerance and social inclusion,” is

a must-see exhibition that explores the deadly conflict between radical leftist groups (i.e. The Shining Path and the MRTA) and the Peruvian government from 1980 to 2000, that terrorized the

population in many communities and left tens of thousands dead and/or disappeared. LUM’s construction was funded by the German government and provides a forum in which to acknowledge the

atrocities, mourn the victims, and celebrate efforts to rebuild inclusive communities. It was both heart-wrenching and heart-warming. After LUM, we shared an excellent meal at the Café de Lima, for which Claudia had designed a stunning and carefully detailed remodel, with a quality of

design and construction craft we had not yet seen in Peru.

We thank all of the Hiromoto family for providing us such an enjoyable and personal perspective on Lima!

Lima's water park

We also ventured out on our own in Lima. At the waterpark in the Parque de la Reserva we attended the very popular (and pretty spectacular) night time light show, and walked past and through the many interactive fountains. The entry fee to the park was quite accessible, which meant that it was packed with thousands of Peruvians, which was great to see.

Día de los muertos

On November 2, Day of the Dead, we visited the huge General El Ángel Cemetery in the old town where a steady stream of family members were bringing flowers to the graves of their deceased. The cemetery had a surprising (to us) number of graves belonging to families that had immigrated to Peru from China and Japan generations earlier, as did the Hiromotos in the 1920s.

Fútbol rivalry

We attended a fútbol game in the fairly new national stadium between two rival teams from Lima: Alianza and the Sport Boys. As we ate dinner near the stadium before the game, several buses and flatbed trucks overflowing with chanting Sport Boys fans, all clad in the team's color pink, sped by on their way to the stadium, each accompanied by police escorts. Throughout the game the chanting by rival fans from opposite ends of the stadium was constant, at near-deafening levels, but all of that energy couldn't change the final score: 0-0.

World record Panamerican cyclist

Finally, we had the privilege of meeting fellow cyclist, Jonas Diechmann from Germany, as he passed (flew!) through Lima on his way to setting the new world record for cycling the Pan American highway unsupported. He cycled 23,000 km from the Arctic Ocean on the northern coast of Alaska to Ushuaia at the southern tip of South America in just 98 days, 2 days ahead of his goal. He finished his epic journey last weekend on November 24, 2018!

For comparison, we have been going 158 days, and pedaled just 3,812 km - so for us, his accomplishment is spectacular and beyond what we can imagine!

Congratulations, Jonas!

Former plantation hacienda

From Lima, we took a 3-day bus tour to visit some of the unique sights on Perú’s south coast. The first stop was a sprawling hacienda that has been beautifully restored into a posh hotel. It was a window into the opulent lifestyle of the Spanish colonists, and the horrible living and working conditions of the enslaved Africans who were smuggled in to the hacienda through underground tunnels (to avoid taxes) to make that lifestyle possible.

Paracas Reserve and the guano islands

Next was the Paracas National Reserve, a desert peninsula with an ancient candelabra-shaped geoglyph of mysterious origin, and a boat ride to the rocky Ballestas Islands, home to hundreds of thousands of guano-producing sea birds. In the late 1800s, a short-lived, but thorough, international frenzy of guano extraction from South America's coastal islands occured, and then turned into the Chincha Islands War, which resulted in Spain eventually signing peace treaties with Perú, Bolivia, Chile and Ecuador. Today, Perú controls the Ballestas islands and the guano resource (now protected by the Reserve), which it still harvests and sells.

Huacachina dunes

We visited an expansive range of sand dunes above the touristy town of Huacachina which is located in a genuine oasis, the first we've ever seen. We enjoyed a roller-coaster of a dune buggy ride, and then filled our shoes with sand as we hiked steeply to an amazing view of the ever-changing, windswept dunes.

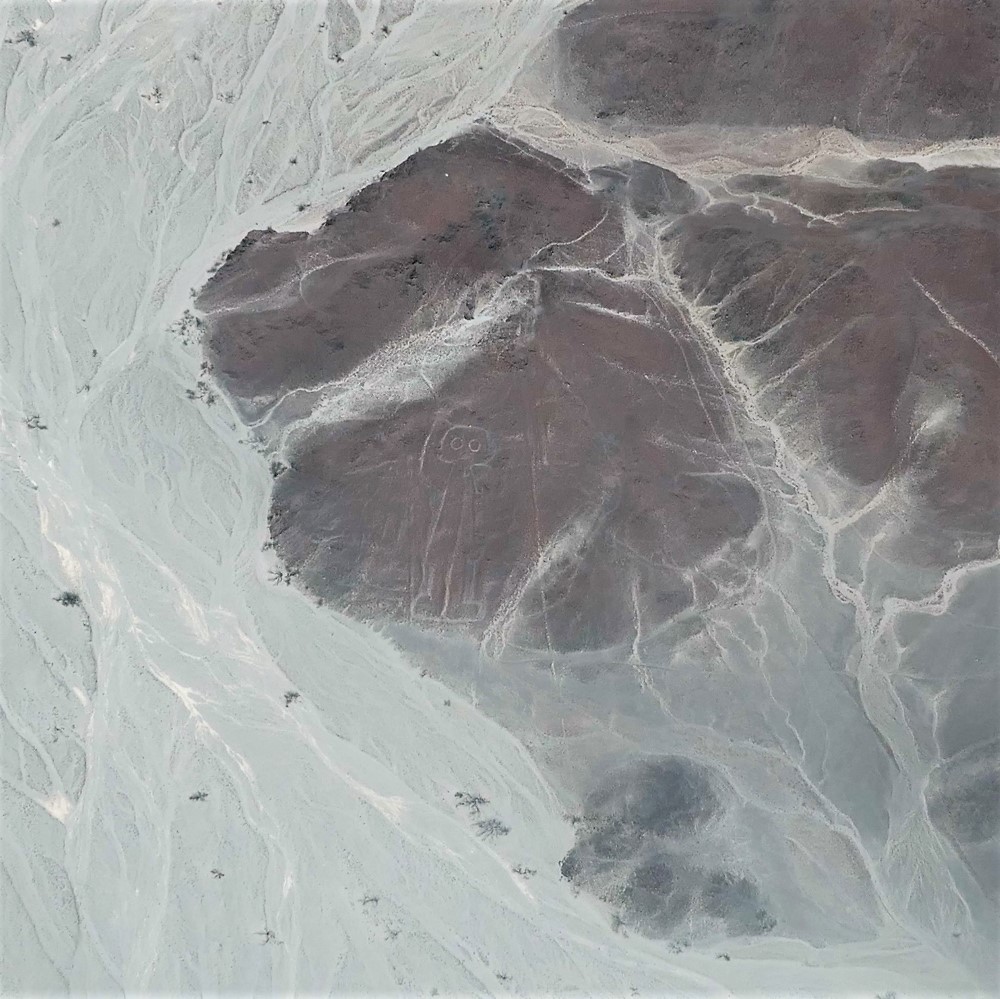

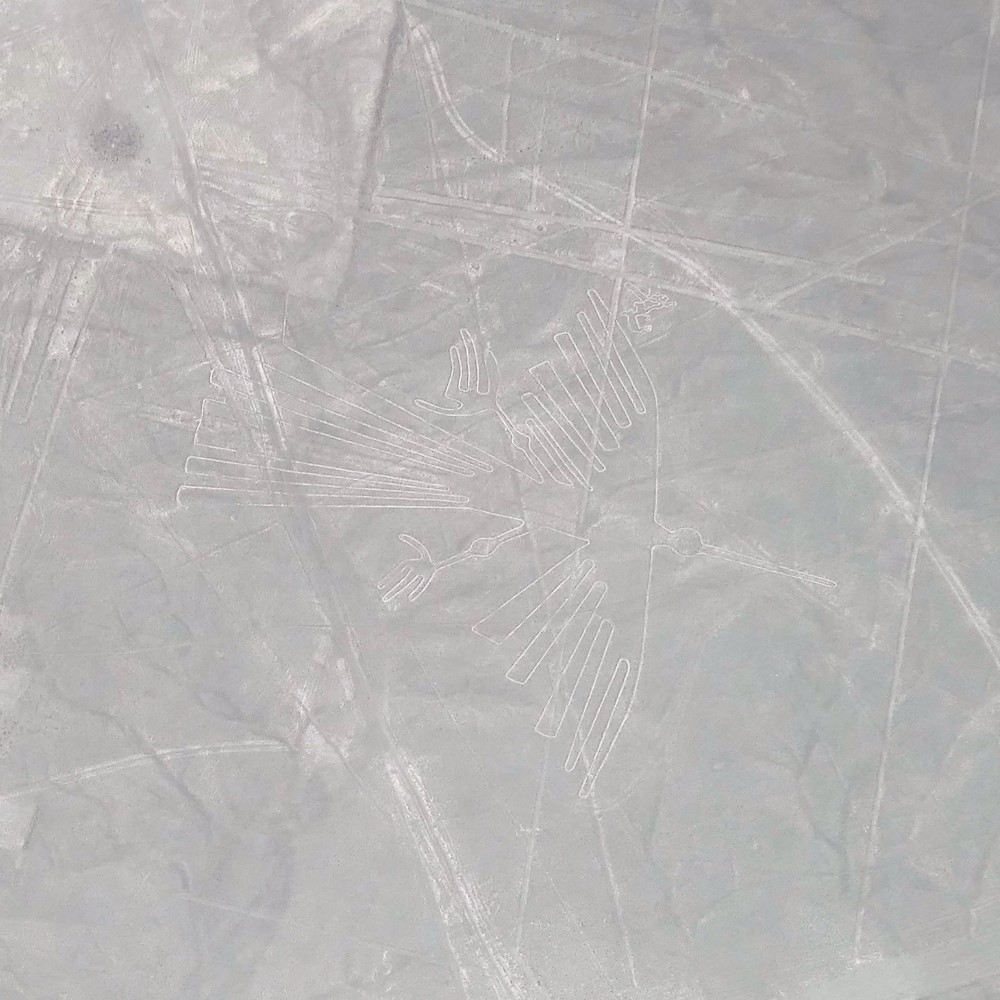

Mysterious Nazca Lines

Finally, we flew in a small plane (with a female Peruvian pilot!) over the Nazca Lines – huge geoglyphs of geometric and animal shapes drawn on the ground (by removing the top layer of dark oxidized rocks and exposing the light-colored rocks just a few centimeters below) such that they can only be seen from above, presumably for the eyes of the gods. There were also puquíos, large spiral wells that were apparently ancient pumps and part of a sophisticated and extensive underground aqueduct system used to bring groundwater to the surface to irrigate fields year-round.

Lasting impressions of Perú

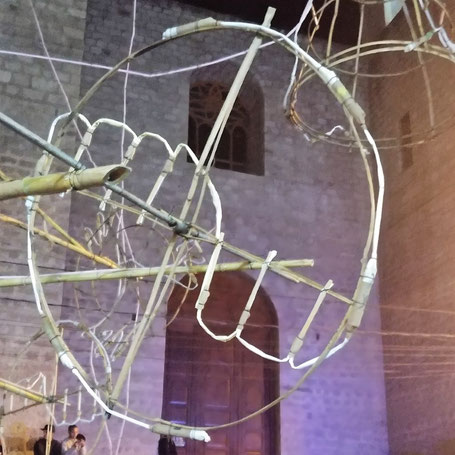

Even though we ended our Perú trip in the big city of Lima, our lasting impressions of Perú will be the sights and sounds of the rural countryside. Earth-colored adobe buildings that are allowed to simply and slowly disintegrate back into the ground when they no longer serve their purpose. Marching bands of brass horns, drums and portable wooden harps accompanying dancers in colorful dress and wearing percussive seeds or shells on their ankles. Fireworks erupting wildly from spindly homemade bamboo structures in celebration of a local school’s anniversary. And lovely exuberant bird songs coming from the bushes and trees all around us (more than we'd heard anywhere else on the trip thus far).

¡Viva Perú!

We are now in Chile, beginning our (long awaited) ride into Patagonia. To find out where we are at any given moment, check our Track My Tour page, where we post a photo and blurb every day that we’re on the move. Also, you can get more up-to-the-minute, spontaneous updates if you follow Clark's accounts on Instagram and/or Facebook.