This blog describes our descent from Bolivia’s high Andes eastward to the jungle lowlands, and back, where we experienced a broad diversity of climates, landscapes, political views, indigenous heritage, and European legacy.

Potosí - city of silver

We’d been riding in Bolivia’s high altiplano, and opportunistically hopped a bus to Potosí. Arriving at dusk, we assembled our bikes, and undertook a challenging, hour-long, 6-km ride from the bus terminal, up steep, winding city streets, during rush hour, to our guesthouse in the old downtown.

Potosí’s historic city center, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is being cleaned and restored to reveal its former wealth, which was generated from the silver mines in “Cerro Rico” (Rich Mountain), that stands prominently behind the city. The Spanish explorers learned of the silver here in 1544, and within 30 years Potosí’s population exceeded that of many European capitals at the time, including London, despite being located in South America’s remote altiplano at high elevation (4,090 m, 13,420 ft).

Potosí mines

Cerro Rico is the world’s most prolific silver mine. Spain used the silver to fund its colonialism for over 200 years, killing a horrifying number of people in the process. The vast majority were enslaved -- first local indigenous people and later Africans.

The mountain is still mined today, primarily for tin and zinc now, by locals who have formed workers’ cooperatives.

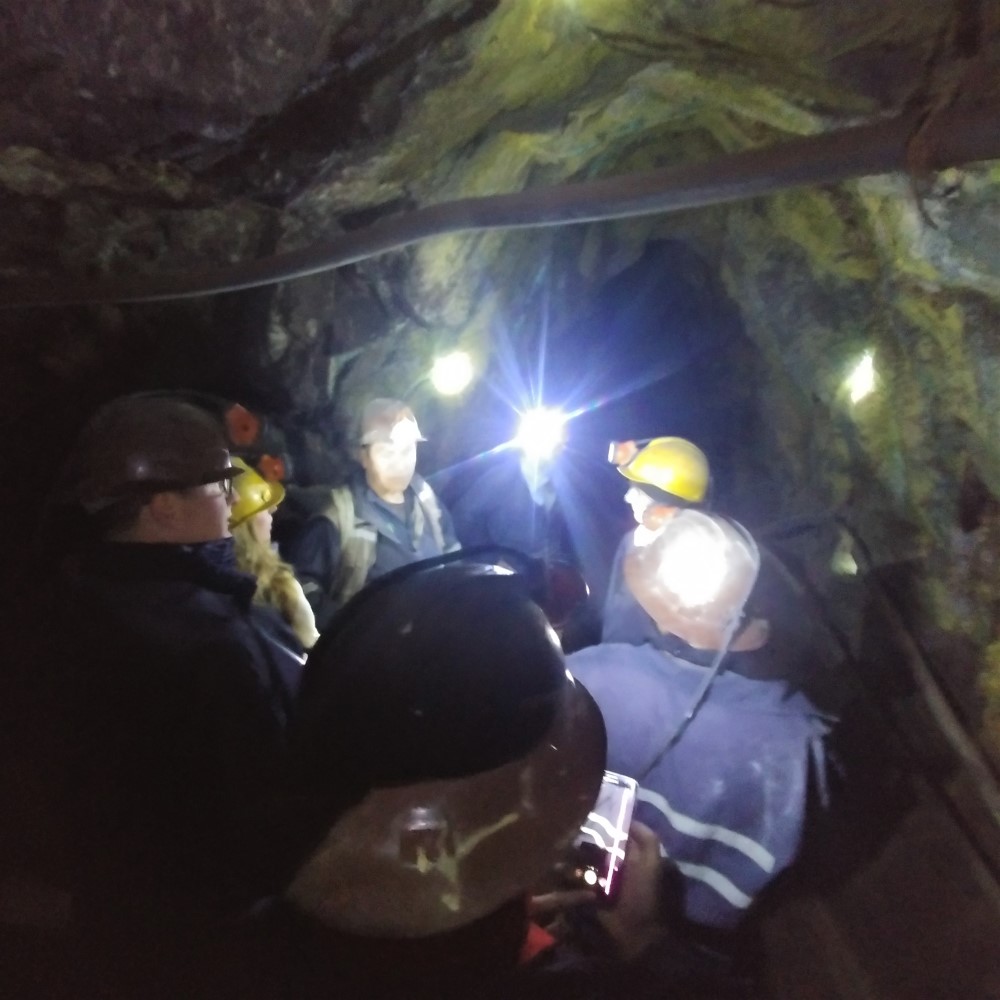

We took a harrowing tour inside the mining tunnels and witnessed the appallingly hazardous conditions in which the miners work.

Apparently there are no safety regulations, no coordination of digging and blasting between competing cooperatives, no structural engineering, and no ventilation, lighting, radios, or other technology investments. Respirators were worn only by the miners actively chiseling rock. The youngest miners (teenagers) breathed the dusty, stale air deeply as they exerted, sprinting in and out of the mine hand-pushing impossibly heavy ore carts along uneven metal or wood rails.

Every miner had a cheek stuffed full of coca leaves, which fuels them for 12 hours shifts of hard labor with no food breaks. The mine opening was blackened from ritual painting with llama blood, and deep inside the mine weekly offerings were made to a statue of “El Tío,” the devil-like guardian of the mountain.

For more, here’s a 20-minute BBC documentary: “The Mountain That Eats Men”.

Potosí mint

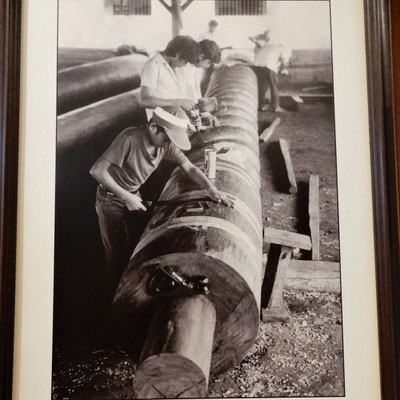

The dangerous work extended to Potosí’s mint - the first in the Americas - where silver was smelted, rolled, and pressed into coins. Potosí’s silver coins became the world’s first global currency, fueling explosive international trade. Galleons full of coins traversed the world, and many were pirated or sunk en route.

The huge mint building is now a well-kept museum that chronicles coin press technology from hand hammer and then screw press, in which many fingers were lost, to steam-driven and ultimately electric presses.

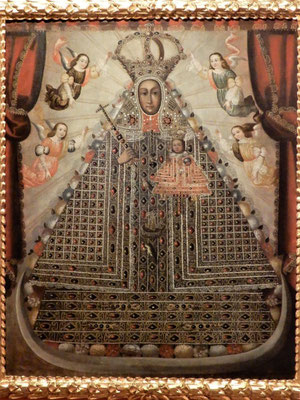

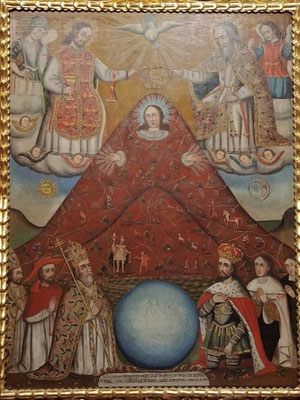

The mint contains beautiful examples of religious art from the region: Mary depicted in the shape of a triangular mountain in the “Andean baroque” style, and clerics with expressive hands in the “Potosí school” style.

Corpus Christi in Potosí

The importance of silver in Potosí’s culture was really on display in its celebration of the Catholic holiday of Corpus Christi. Catholic school students decorated the roadway around the cathedral plaza with carpets of colored sawdust, lined with faux silver bars, while their parents erected wooden frames hung with all kinds of silver platters, chalices and utensils.

During a slow, beautiful procession, the symbolic body of Christ was carried around the plaza, passing under each archway, accompanied by the schools’ marching bands.

Before the procession began, vendors were selling mountains of “chambergos” (puffed sticky bread) for the occasion.

After the procession ended, the faithful immediately swept up the colored sawdust and disassembled the frames, leaving no trace, other than the helium balloons headed ever skyward.

The next morning people returned to the plaza to share a traditional Andean meal of boiled corn, fava beans, potatoes, “chuño” (rehydrated freeze-dried potatoes), cheese, and “charque” (shredded, dried llama meat). We were generously offered a free plate.

As in the rest of Bolivia, we felt totally safe in Potosí, and enjoyed exploring the old city streets and its colonial architecture.

When it was time to leave Potosí by bike, we avoided its steep hills by following a route recommended by Renan, our guesthouse manager and bike enthusiast.

Clark’s Achilles tendon was feeling a lot better, and soon we were pedaling downhill on pavement, from the high, golden altiplano to the Mediterranean-like climate of Bolivia’s judicial capital, Sucre, at the less extreme elevation of 2,810 m (9,220 ft).

President Evo Morales

The road was lined with newly painted campaign signs that, without exception, promoted a fourth (and unconstitutional) term for the current president, Evo Morales.

Evo is a controversial figure in Bolivia. He is generally credited with Bolivia’s strong economic growth, reduction in poverty, and increase in literacy. He is very popular, especially in the altiplano, for his infrastructure investments in paved roads, water, electricity, and sports fields, and his redistribution of agrarian land to indigenous communities. He is unpopular in many of the largest cities, including capitalist-leaning Santa Cruz in the resource-rich eastern lowlands. Bolivians were not shy about sharing their thoughts about Evo with us. Whether they liked or hated his policies, most felt he was corrupt and had become a dictator. In 2016 he sought, and lost, voter approval to run for a fourth term, so he got the court eliminate term limits altogether, finding them to violate a politician’s human rights. He could have left office this year as a national hero, but instead he’s clinging to power. Note: the election occurred recently, and people are now in the streets protesting Evo’s claim of a narrow victory.

Riding to Sucre

Riding to Sucre, we overnighted in the spartan accommodations of a kind woman who rented us a single straw bed in a storeroom (we opted to spread our sleeping pads and bags on the floor). The shared bathroom had a hot shower, with tape on the faucet handle to minimize the electric shock that we’ve learned to anticipate with these ungrounded electric showerheads.

At the restaurant next door, we ate a grim dinner of overcooked chicken and fries, and wondered how men at the next table drank beer without swallowing the golf-ball sized wad of chewed coca leaves in their cheeks.

Sucre - the white city

Sucre was founded by the Spanish colonists to be near the action in Potosí, but in a much more comfortable climate. It was the original capital of Bolivia, but now retains only the judicial branch (the legislative and executive branches were moved to La Paz).

Known as the “white city” for its well-preserved whitewashed Spanish colonial architecture, Sucre has a charming, well-maintained historic center with lots of shade-filled manicured parks. It’s another UNESCO World Heritage site.

Our gorgeous hillside guesthouse was tough to reach by bike, but it was so comfortable that we, like many travelers, ended up staying a while to rest.

At the guesthouse we watched the partial solar eclipse through glasses we had brought from the US. In planning the trip, we had hoped to experience the total eclipse in Argentina, but traveling with the seasons for optimal riding weather put us too far north.

Two museums were the highlight of our stay in the city of Sucre. First was the museum of indigenous arts, which displayed the varied textile designs employed by men and women in different indigenous groups near Sucre, and the costumes of their traditional dances.

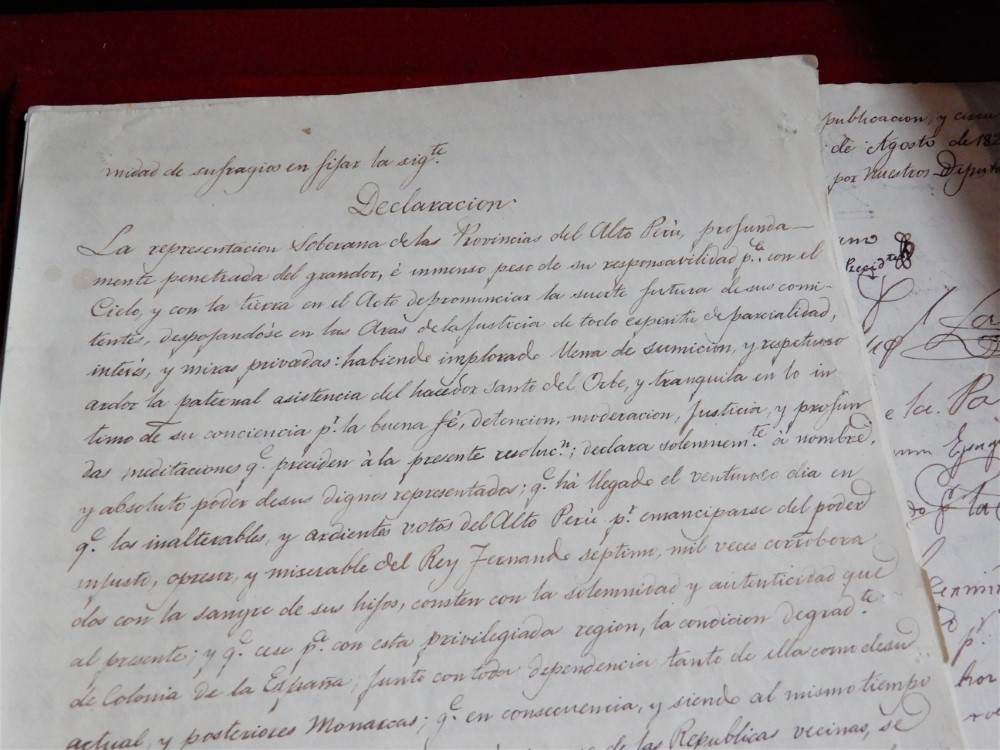

Second was the Casa de la Libertad, Bolivia’s version of the US’s Independence Hall in Philadelphia. It is where Bolivia signed its Declaration of Independence from Spain — the last country in South America to do so. Bolivia’s legislature then assembled there, until it moved to La Paz. The building was originally a Jesuit university (until they were expelled from South America in 1767) that educated a number of Bolivian revolutionaries who led the move to independence. We got a fascinating tour in English.

Maragua Crater hike

Sucre sits amidst impressive colorful geology that was once home to dinosaurs. We explored it on a 3-day guided hike to the “Maragua Crater.”

The hike began at a pass with a monument to Tomás Katari, a Quechua leader that tried, but failed, to peaceably gain independence from Spain for the Indians. There was a small chapel with a Andean-baroque image of a triangular Mary painted on a rock, surrounded by offerings of coca leaves and beer.

We hiked down a portion of stone-paved Inca trail that had undergone a heavy-handed restoration, crossed a new pipeline that carries water to growing Sucre, and descended to a river valley. A 10-year old girl collected her community’s entrance fee from us before we crossed a very twisted suspension bridge.

On the other side we ascended past a creek that flowed in natural canals carved out of hard layers of sediment, with our out-of-shape guide struggling to keep up, and then down into the Maragua Crater.

It’s not really a crater, but rather a broad bowl formed when deep layers of ancient sediment folded up accordion-style under pressure of tectonic plates. Check out this satellite view. The layers have become beautifully exposed by erosion.

Inside this bowl is a small Quechua-speaking community that farms wheat, grows carnations in greenhouses as a cash crop, and runs a hostel, where we were the only guests for the night. Our chatty English- and Quechua-speaking guide, David, cooked a vegetarian dinner there for us.

On the second day we walked to the Garganta del Diablo — a tall cliff covered in hanging plants, noisy parrots and a limestone cavern — over which the river that drains Maragua Crater falls. We then crossed the “crater,” climbed the swirly strata to its west rim, and dropped into another valley of colorful rock layers, sharing our coca leaves with the few locals we met along the way.

At Niñu Mayu, a tiny, autonomous village without electricity, we saw incredible dinosaur footprints in an uplifted, sloping ancient mud layer.

We spent the second night in another community-run hostel in the farming town of Potolo, and awoke on the third day to the early morning calls of roosters and burros. We returned to Sucre in a crowded trufi (minivan transport) filled with elder locals and a few children (21 people in total), and the herbaceous smell of people chewing coca leaves.

Dinosaur footprints galore

We saw even more evidence of dinosaurs that roamed the area 68 million years ago at Parque Cretático, just outside Sucre. The park contains a remarkable 5,000 very visible dinosaur footprints of at least 8 different dinosaur species. The spectacular trails of footprints meander across a huge, now-vertical wall of mudstone (100 m high and 1.5 km long) that was uncovered in 1994 in a commercial lime quarry at a cement factory. One large section of the wall has collapsed, exposing yet another layer of mudstone with more footprints!

The park, built on the cliff above the still-operating quarry and factory, contains well-done life-size replicas of the different dinosaur species. We enjoyed an educational tour by an animated English-speaking guide who employed plastic dino props in his explanations.

Riding from Sucre

As we pedaled out of Sucre, past the cement plant/dino park, we rode a few kilometers with Alejandro, a young cycling enthusiast who was also riding to Santa Cruz, but in half the time as we.

That night we camped with permission on a little-used covered basketball court in the teensy village (just 3 families) of Puente Arce. We were visited by piglets, goats, a howling cat, several dogs, and most importantly, by two outgoing teenage girls, Marisela and Stefani, who brought us mandarins, blew up our sleeping pads, drank from our Camelbaks, tasted our soup, and played inside our tent as we prepared for bed. We were not the first bike tourers they had hosted, and we were glad they had a positive impression of foreigners.

At the end of the next riding day we hopped on a bus in order to get to a town where we could watch the US women’s soccer team play in (and win!) the World Cup finals.

Samaipata

That town was Samaipata, a funky hilltown getaway for residents of Santa Cruz, offering cool weather, vineyards, the Amboró National Park, and Inca ruins that include a solid rock hilltop carved up for ritual uses.

We took two hikes with Michel, a German-Argentinian biologist. The first was through a primordial-feeling forest of endemic giant tree ferns.

The second hike was to views of vertical red sandstone cliffs jutting up through forested hills. After the big landscapes and vistas of the altiplano, it was a great chance for us to focus on Nature’s small details in a unique forest.

Ride to Santa Cruz

From Samaipata we pedaled 120 km to Santa Cruz (elevation 400 m, 1,300 ft) in one day, descending steadily at river grade. We stopped en route at the town of El Torno’s central plaza and succeeded in spotting one of the sloths that we’d heard live there. And finally, Clark’s Achilles tendon felt perfect all day!

Santa Cruz de la Sierra - Bolivia's largest city

Santa Cruz de la Sierra is Bolivia’s largest city, whose economy is driven largely by agribusiness and petroleum. The city itself was not our reason for traveling this far from the Andes, but we did enjoy a nice outdoor art exhibit there, and celebrated our anniversary at a great Mexican restaurant.

Jesuit mission circuit

We came to Santa Cruz to visit the carefully restored Jesuit missions of Chiquitos — another of Bolivia’s UNESCO World Heritage sites. We left our bikes and gear in the hotel, rented a car, and embarked on a 4-day clockwise 1,000 km-loop to visit 7 of the historic missions.

The road passed through large-scale agriculture and then through tropical dry forest with large areas cleared for grazing of heat-tolerant white brahman cattle, and filled with termite mounds We spotted toucans, parrots, peccaries and rheas. We also passed several Mennonite communities.

Jesuit missionaries came to this area in the 1600s. They were successful in converting the indigenous people and built numerous missions that operated as self-sufficient communities with semi-autonomy from the Spanish crown, helping to protect the locals from slavery until the Jesuit expulsion in 1767. The Swiss Jesuit priest and musician, Martin Schmid, was largely responsible for the design and construction in the 1700s of the mission buildings we see today. Another Swiss Jesuit, architect Hans Roth, undertook the complete restoration of the missions, starting in 1972.

Common features of all the missions are a large barn-like church (which interestingly resembles a Swiss chalet with a low-sloped gable roof and large overhangs), a freestanding bell tower, and an outdoor square surrounded by long one-story buildings with covered arcades. Entire trees were used for columns and beams in the churches. The buildings are decorated with spectacular ornamentation combining indigenous and European aesthetics.

The original constructions and the faithful renovations were carried out by local artisans trained in woodcarving, carpentry, plaster, paint and gold leaf. These buildings are without a doubt some of the most striking and beautiful churches that we’ve seen anywhere in the world!

San Javier Mission contained musical instruments built in the mission, and its ceiling and interior columns were painted.

Concepción Mission had a museum documenting the renovations.

San Ignacio Mission was completely demolished before being rebuilt in its original style, and therefore does not have a UNESCO designation. It includes some bright mica mosaics.

At the San Miguel de Velasco Mission, we met 75-year old Carmelo, who led a carpentry team in the renovation. He revered Hans Roth for his superb, precise planning that allowed complete renovation in just 3 years.

San Rafael de Velasco Mission had cane ceilings and included old mica mosaics in the altar, pulpit and one wall.

Santa Ana de Velasco Mission had attractive, simple ornament, and its white paint sparkled with tiny flecks of mica.

San José de Chiquitos Mission had a unique stone facade and many layers of frescoes on the arcade walls. It was barely saved from demolition in the 1950s.

San José de Chiquitos - the original Santa Cruz

In San José, our guesthouse owner, Aidee, served us “cuñapes” (chewy cheese bread made from tapioca flour) hot from the outdoor clay oven, and explained the “abuelo” masks that locals used to make fun of the white Spanish invaders.

Her husband, Johan, who was also the City Manager, took us to a cliffside view over the valley and gave us a tour of the ruins of the original Spanish settlement of Santa Cruz that was soon abandoned due to insects, attacking natives, and lack of water.

Cochabamba

After returning to Santa Cruz, we loaded up our bikes, rode to the bus station, and began a long bus journey to La Paz. We had decided that we wanted to spend the last days of our South American bike journey riding and hiking in the mountains, rather than ascending slowly from the jungle back to the altiplano. We broke the bus ride into two days, for both comfort and acclimatization, as we would be ascending from 400 m to 4,000 m (1,300 ft to 13,000 ft). It rained on the way to Cochabamba, and we were glad to be on the bus.

During our one-day layover in Cochabamba, we visited the beautifully renovated Santa Teresa convent and sampled the nuns’ cookies, climbed the hill to the enormous statue of Jesus Christ, and witnessed yet another march in the street, this time a worker protest.

Bus to La Paz

On the bus to La Paz, after it made a quick stop for a hot lunch and a restroom break, an evangelist boarded and engaged the crowd in a long, passionate sermon. After successfully collecting alms, he stuck around to expound the miraculous properties of his herbal soap… and sold a few bars. Shortly thereafter traffic stopped for an hour at a high pass. It was snowing and we saw that there had been a horrible accident on the road.

We arrived in La Paz just after sunset, and enjoyed an exhilarating twilight ride 5 km downhill through the winding, busy city streets to our guesthouse. La Paz is a big, high-altitude city that sits at the feet of even higher snow-capped peaks. From there we will do some mountain trekking and visit Lake Titicaca, then we will ride north to Cusco, Peru, where we will end the biking portion of our South American journey. Stay tuned for those stories in the next blog.

We're posting this blog upon landing back in the United States after 17 months in South America! Our travels are over, but our blog is not... There are more stories to tell, from the completion of the cycling portion, to travels with friends around Buenos Aires and Brazil, so stay tuned! To see our whole journey, check our Track My Tour page. You can review past social media posts on Clark's Facebook and Instagram accounts.